The Problem

Molecule-based magnets like vanadium tetracyanoethylene are extremely sensitive to air, impeding their use in practical quantum devices.

Molecule-based magnets like vanadium tetracyanoethylene are extremely sensitive to air, impeding their use in practical quantum devices.

Researchers coated vanadium tetracyanoethylene with an ultrathin, transparent layer of alumina using low-temperature atomic layer deposition to stabilize the material while preserving its magnetic properties.

This approach allows scientists to study the material in detail and makes it compatible with superconducting circuits, paving the way for scalable quantum technologies.

Professor Mark Hersam, Postdoctoral researcher Iqbal Utama

Quantum information technology is an emerging field that McKinsey projects could reach a $100 billion market within the next decade. The field focuses on developing next-generation computing that enables faster information processing and more secure communication, with the potential to transform areas such as finance, drug development, and cybersecurity.

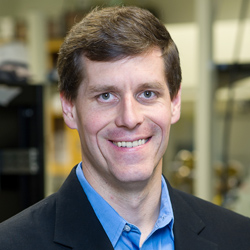

A promising method for connecting quantum devices on a chip is to use magnons, magnetic waves that move through materials and carry information. Recent research from a team led by Professor Mark Hersam found that a fragile magnetic material called vanadium tetracyanoethylene can be protected from atmospheric damage by coating it with an extremely thin layer of alumina.

This coating, added through a gentle, low-temperature process, provides protection for months while preserving magnetic properties. Because the alumina layer is thin and transparent, scientists can still study the material using light and other tools that need to be close to its surface.

This breakthrough allows researchers to explore the material’s natural behavior in much greater detail than before.

“These results establish a viable and scalable encapsulation strategy for molecule-based magnetic materials, opening the pathway to their use in hybrid quantum technologies,” Hersam said. “The ability to process and handle vanadium tetracyanoethylene by making the material stable in air represents a key step toward practical quantum hardware that incorporates magnonic materials.”

Hersam is the chair of the Department of Materials Science and Engineering and Walter P. Murphy Professor of Materials Science and Engineering at the McCormick School of Engineering. He also is director of the Materials Research Science and Engineering Center, and a member of the executive committee for the Institute for Quantum Information Research and Engineering. Along with lead author and postdoctoral researcher Iqbal Utama, Professor George Schatz, and colleagues from The Ohio State University and Cornell University, Hersam presented the work in the paper "Enabling Ambient Stability and Quantum Integration of Organometallic Magnonic Ferrimagnets via Atomic Layer Encapsulation," published Nov. 26 in Nature Communications.

Mark HersamWalter P. Murphy Professor and Chair of Materials Science and Engineering

Molecule-based magnets like vanadium tetracyanoethylene have long shown promise for quantum technologies, but they are so sensitive to air that they’ve been nearly impossible to use in real devices. This new work solves that problem by providing an ultrathin encapsulation layer, making it compatible with the kinds of superconducting circuits used in quantum computers. The protective coating also allows scientists to perform experiments that were previously out of reach — such as using optical microscopies and spectroscopies to directly observe magnetic patterns and study how light and magnetic waves interact at extremely low temperatures. These advances give researchers a much deeper understanding of how the material works and moves it closer to being used in practical, scalable quantum systems.

This research builds on earlier findings that vanadium tetracyanoethylene can carry magnetic waves, or magnons, with almost no energy loss — making it one of the best materials for transmitting quantum information. However, past efforts to protect it used a thick epoxy coating, which was too bulky and didn’t work well for the cold and high-frequency conditions needed in quantum devices.

“The current study introduces a nanometer-thin, conformal atomic layer deposition alumina layer that provides equivalent protection while allowing optical transparency and cryogenic compatibility, thus overcoming previous limitations,” Hersam said.

![This is an alumina-encapsulated V[TCNE]ₓ device integrated into a microwave superconducting resonator chip, shown as it is being loaded into a sub-Kelvin cryogenic refrigerator. The dark brown vertical strip on the chip is the alumina layer.](../../../../../images/news/2025/11/new-coating-method-stabilizes-fragile-magnetic-material-for-next-generation-quantum-devices-body.jpg)

Next, researchers plan to apply this alumina coating method to other molecule-based magnetic materials to build fully integrated quantum chips. These chips would link tiny magnetic spins with superconducting qubits or light-based (photonic) devices, advancing hybrid quantum technologies.

By fine-tuning the coating layers, scientists also hope to transfer magnetic signals between different quantum materials—a key step toward more versatile quantum computers. Because the alumina layer is so thin, it will also allow closer interrogation of the detailed magnetic behavior inside the vanadium tetracyanoethylene film.